We are medical experts, but it’s not enough on its own.

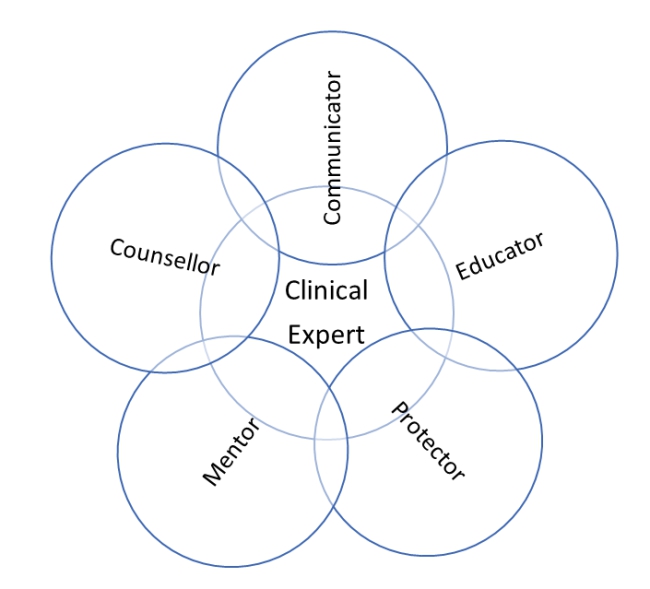

We pride ourselves on being an expert in our field, and rightfully so. In our profession, so much of what we do revolves around what we know and what we can physically do for our patients, and as a result, much of our professional life is spent cultivating our knowledge and technical skills. This is also reflected in many professional frameworks around the world, including the CanMEDS framework which centralizes the physician’s role as a Medical Expert.1 While this role is crucially important and is essentially what makes us physicians, it is important to remind ourselves of our other vital roles and the part they play in patient-provider communication, especially when delivering bad news. In addition to Medical Expert, the CanMEDS role framework also depicts six other interconnected roles: communicator, collaborator, professional, leader, scholar and health advocate (Figure 1).1

.png)

Figure 1. CanMEDS framework. 1

It seems even these clearly defined roles are subject to change. A recent qualitative study by Caulfield et al. (2020) evaluated the validity of these traditional roles during the communication of poor prognosis in Ghana through the consideration of the Positioning Theory, which states that an “individual’s choice of action is affected by local moral context, through explicit attention to the role of rights and actions within an interpersonal encounter”.2 In interviews with physicians who were experienced with communicating poor prognosis, the situational roles physicians adopted during these types of conversations were analysed. The results of this analysis show that physicians adopted six positions while giving bad news: clinical expert, educator, counsellor, communicator, protector and mentor (Figure 2).2

Figure 2. Physician positions during the communication of poor prognosis.2

Interestingly, two new roles emerged that do not appear in other frameworks, counsellor and protector, and both seem to be based more on inherent qualities rather than trained skills.2 While physicians in this study identified ‘clinical expert’ as their default position, they also reported that this quality would be meaningless without other skills, particularly good communication skills in the case of communicating poor prognosis.2 These findings support the centrality of the ‘clinical expert’ role as well as the interconnectedness of all roles depicted in the CanMED framework. However, this study found that physicians in different cultural and situational settings may assume different roles and therefore suggests that we interpret these roles with much less rigidity depending on our context. Caulfield et al. (2020) also suggest that perhaps the use of the term ‘positions’ might be more appropriate as it tends to better reflect this fluidity.

It seems that being a skilled communicator has less to do with how rigidly we adhere to distinct roles and more to do with our ability to apply them in a more local context – especially if we are to “create physicians who are socially accountable to the communities they serve”.2

Being a Good Communicator is No Easy Task

It is impossible to know everything there is to know about communication; add bad news to the mix and we are all bound to feel a little uncomfortable. However, some physicians might be feeling a little more comfortable than others. In a study by Barnett (2002), 106 patients were interviewed to assess their perceptions of physician helpfulness in breaking bad news (for all physicians involved in their care). Overall, surgical specialists were significantly more likely to be rated poorly by patients compared to their non-surgical specialist or general practitioner peers. In fact, of the physicians rated ‘least helpful’, all were surgical specialists.4 This is an interesting observation, especially considering that surgical specialists might need to break bad news more routinely in their practice. Would this not make surgeons more effective in breaking bad news? Perhaps not. Surgical specialists may be at a disadvantage when it comes to breaking bad news. For example, surgeons generally do not have the time-frame that other practitioners do to develop the same type of relationship with their patients. This highlights the need for increased attention when it comes to developing communication skills further in surgical specialties.4

For more insight on the specific challenges involved in the communication of poor prognosis, we look to clinical oncologists who, unfortunately, routinely experience situations where they must navigate conversations on poor prognosis. Although the specific ways in which they interact with their patients may differ, their experience can teach us a lot about breaking bad news.

The results of a 1998 survey of participants (n = 500) at a Breaking Bad News Symposium organized by the American Society of Clinical Oncology revealed that 45% of participants needed to break bad news to a patient more than 10 times per month.5 Participants reported that the most difficult part of breaking bad news was being honest without taking away hope, followed by dealing with the patient’s emotions and spending the right amount of time with patients. Overall, 67% described themselves as ‘not very uncomfortable’ or ‘uncomfortable’ when dealing with a patient’s emotions. When asked about formal education for breaking bad news, only 5% said they had received formal training, 39% said they learned by sitting in with other clinicians during a meeting for breaking bad news, 14% said they had received both formal training and the chance to sit in with other clinicians, and 42% said neither. Just under half of participants rated their ability to break bad news as fair, poor or very poor (Figure 3).5

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Figure 3. Survey results from the Breaking Bad News Symposium (1998).5

Medical education has changed since this survey was completed, but nevertheless, results like these continue to motivate modifications to our medical curriculums. Without a formal communication curriculum, physicians will be relying on chance encounters with life-altering conversations during clinical rotations to develop this skill.6

Meeting Patient Expectations

Finding out what patients expect is an important step in towards becoming a better bad news communicator. Results from a study by Ptacek et al. (2001) suggest we can start by creating a comfortable environment and allotting a good amount of time to spend with our patients. Patients in this study also stated that special attention should be given to empathizing with the patient’s experiences.7 Results from other studies report that, despite our instinct to protect patients by providing limited information, most patients actually have high information needs and prefer a good degree of clarity.8,9 Patients also prefer to be involved in treatment decisions and to have the opportunity to ask questions, and stressed the importance of physicians taking the time to help them build up an understanding of their condition.8,9

A study by Richter et al. (2015) examined patient’s preferences in three different age groups: young, middle-aged and elderly adults.10 Overall, results revealed no significant difference between groups in their preferences for the communication of bad news. However, there was a significant difference that existed for younger patients and the value they placed on professional expertise. These findings suggest that younger adult patients might prefer more detailed information and that in general, we can make the same considerations for these types of conversations with all of our adult patients.10

Guidelines

The SPIKES protocol is a popular guiding tool for these types of meeting with patients. The six-step strategy outlined in the SPIKES protocol is described by Baile et at. (2000).5

- S – Setting up the Interview.

- Arrange for some privacy

- Involve significant others

- Sit down

- Make a connection with the patient using eye contact or physical touch

- Manage time constraints and interruptions

- P – Assessing the patient’s perception.

- Use open ended questions to assess patient understanding

- Developing a deeper understanding through questioning will help to tailor the bad news to the patient’s expectations, knowledge and overall way of thinking.

- I – Obtaining the patient’s invitation.

- The majority of patients have a desire for the truth

- Asking a patient about their desire for information can also help reduce personal anxiety associated with delivering the bad news.

- K – Giving knowledge and information to the patient.

- Give a warning that bad news is coming

- Use language that matches the patient’s comprehension

- Avoid excessive bluntness

- Give information in chunks and check in on understanding periodically

- Avoid phrases that suggest “there is nothing more we can do” – there are ways to continue the conversation to discuss pain control and symptom relief.

- E – Addressing the patient’s emotions with empathetic responses.

- Observe for emotion

- Identify the emotion

- Identify the reason for the emotion. If you are unsure, ask the patient.

- Give the patient time to express their feelings

- Express empathy and your understanding of the situation.

- Make an empathetic statement like “I wish the news were better”

- Connect the emotion and the reason for the emotion in a statement like ““I can tell you weren’t expecting to hear this”

- If emotions are not clearly expressed, use more exploratory questions like “Could you tell me what you’re worried about?”

- Until emotion is cleared, it will be difficult to carry on the conversation. Stay here with patients and explore their feelings more if needed.

- S – Strategy and summary.

- Ask if patients are ready to talk about a treatment plan

- If yes, involve the patient in the development of a treatment plan. This will also help share the responsibility of decision making and eliminate any anxiety or fear over future treatment success.

Past research suggests that the SPIKES protocol has yielded significant improvements in self-efficacy among learners and pediatric physicians.6 Survey results from the Breaking Bad News Symposium in 1998 also suggest that physicians feel the SPIKES guideline makes sense and is practical to use. However, over half of participants said that they had several techniques that they consistently used but did not have an overall plan (Figure 4). These results are in line with the findings from the Caulfield et al. (2020) study that stressed the importance of considering each patient and each situation differently.2 Seifart et al. (2013) also examined patient satisfaction of the SPIKES protocol in Germany and found that the protocol produced a significant difference between patient expectations and reality for bad news delivery.8 While factors relating to the specific communication skills and styles of the physicians were not taken into account, these results suggest that rigidly adhering to a specific guideline might not be enough and that patient preferences for the delivery of bad news may vary from patient to patient and region to region.8

.png)

.png) Figure 4: Survey results for the Breaking Bad News Symposium (1998). 5

Figure 4: Survey results for the Breaking Bad News Symposium (1998). 5

The Takeaway

- Consider the context. Your ability to adapt your approach to each unique situation and change roles as needed will be your greatest tool. Spend time developing an understanding of each patient and take into account their specific situation, what they know and what they expect.

- Get comfortable with emotions and learn to respond to them. If you find this part particularly challenging, you can start small by learning a few validating statements that can help to express empathy and support patients through these difficult moments.5

- Involve patients and take the time to provide them with as much information as they feel comfortable with. Most patients want information and to be involved in treatment planning.8,9 Patient’s may state a preference to have less information and that’s fine. The fact that you checked means you are already on the right track.

- Address your fears. Certain underlying fears might affect our success in communicating bad news, such as a fear of being blamed, fear of the unknown and the untaught, fear of expressing emotion, fear of not knowing all the answers, and a personal fear of illness and death.11 Developing tools and tactics or following a guideline might help you work through any fears you may have.

- Talk to Someone. Talk through your approach with a colleague, brainstorm best practices in a group, and actively look to develop this skill. The overall experience of delivering bad news is also very emotional and can cause physicians to feel stressed well after the meeting is over.12 Develop a good support network and plan to deal with this stress. Just as your patients will benefit from talking though their feelings, so will you.

References

- Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. CanMEDS: better standards, better physicians, better care. Royal College Website. Accessed on June 9th, 2020. Retrieved from: http://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds-framework-e

- Caulfield A, Plymouth A, Nartey YA & Mölsted-Alvesson H. The 6-star doctor? Physicians’ communication of poor prognosis to patients and their families in Cape Coast, Ghana. BMJ Global Health 2020;5:e002334. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002334

- Truog RD (2005). Communicating with patients and families in times of stress: Can we do better? Society for Pediatric Anesthesia. Retrieved from: http://www5.pedsanesthesia.org/meetings/2005winter/man/AAP%20Lecture.pdf

- Barnett MM. Effect of breaking bad news on patients’ perceptions of doctors. J R Soc Med 2002;95:343–347. Retrieved from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/014107680209500706

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale, EA & Kudelka AP. SPIKES – A six step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. The Oncologist 2000;5(4):302-311. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302

- Wolfe AD, Denniston SF, Baker J, Catrine K, Hoover-Regan M. Bad news deserves better communication: a customizable curriculum for teaching learners to share life-altering information in pediatrics. MedEdPORTAL 2016;12:10438. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10438

- Ptacek JT & Ptacek JJ. Patients’ perceptions of receiving bad news about cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2001;19(21):4160-4164. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2001.19.21.4160

- Seifart C, Hofmann M, Bär T, Knorrenschild JR, Seifart U & Rief W. Breaking bad news – what patients want and what they get: evaluating the SPIKES protocol in Germany. Annals of Oncology 2014;25:707-711. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt582

- Brown VA, Parker PA, Furber L & Thomas AL. Patient preferences for the delivery of bad news – the experience of a UK cancer centre. European Journal of Cancer Care 2011;20:56-61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01156.x

- Richter D, Ernst J, Lehmann C, Koch U, Mehnert A, Friedrich M: Communication Preferences in Young, Middle-Aged, and Elderly Cancer Patients. Oncol Res Treat 2015;38:590-595. https://doi.org/10.1159/000441312

- Buckman R. Breaking bad news: why is it still so difficult? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984; 288:1597. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.288.6430.1597

- Ptacek, J., Fries, E., Eberhardt, T. et al. Breaking bad news to patients: physicians’ perceptions of the process. Support Care Cancer 7, 113–120 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1007/s005200050240

Please Login or Join to leave comments.